Monday Muse: Harold Cohen & AARON

On my trip to the LACMA this month, I was excited to take in Coded: Art Enters the Computer Age, an exhibition centered around the use of computers in art making from the 1960s through the 1980s. Since I have delved into the realm of AI art lately, feeling both somewhat troubled by the capabilities and inspired by the capacity for dreaming, I was excited to learn more about how we got here. We may feel like AI art is something new, especially since it’s captured the recent zeitgeist. However, artists like Harold Cohen have been utilizing computer programs to make art since the 1960s.

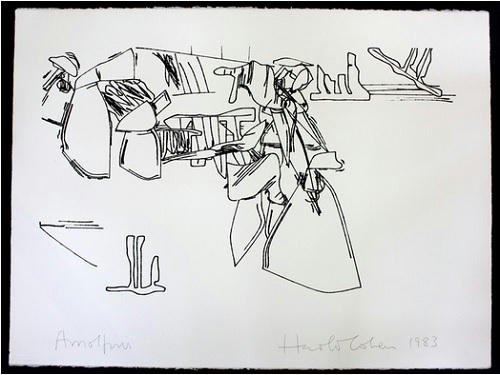

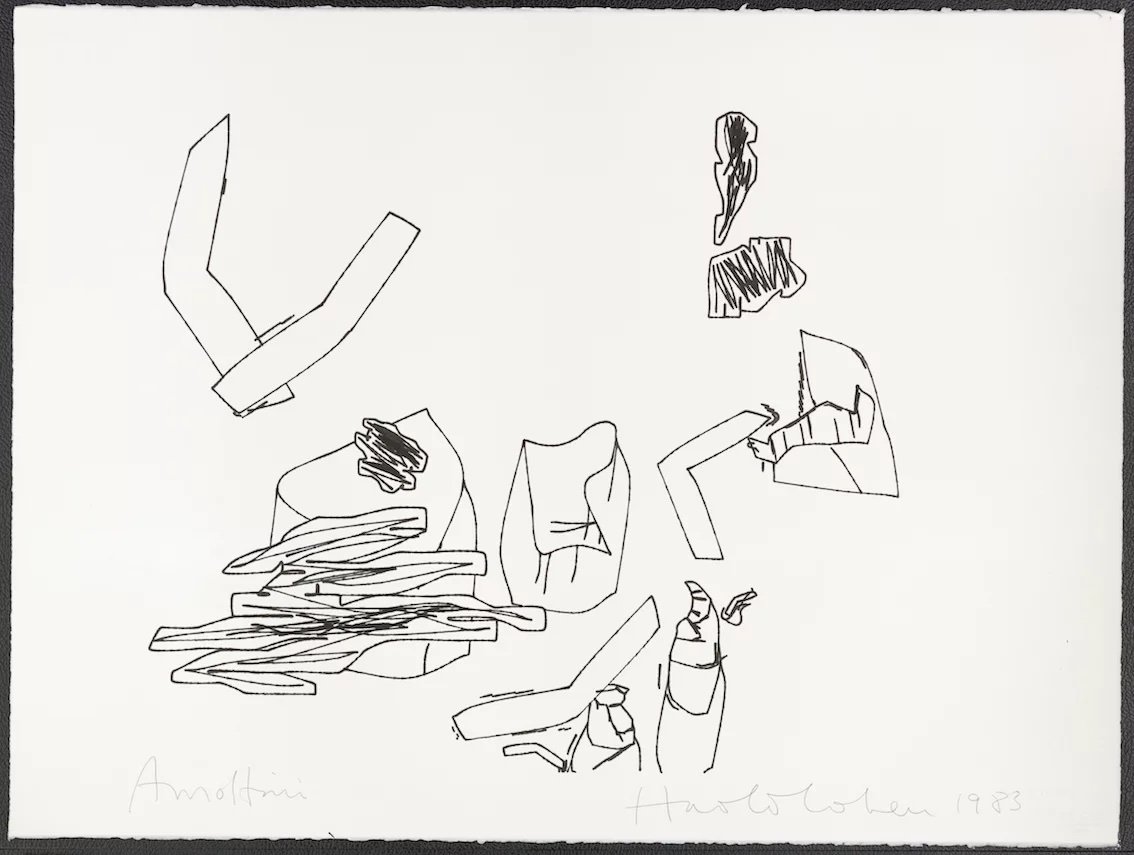

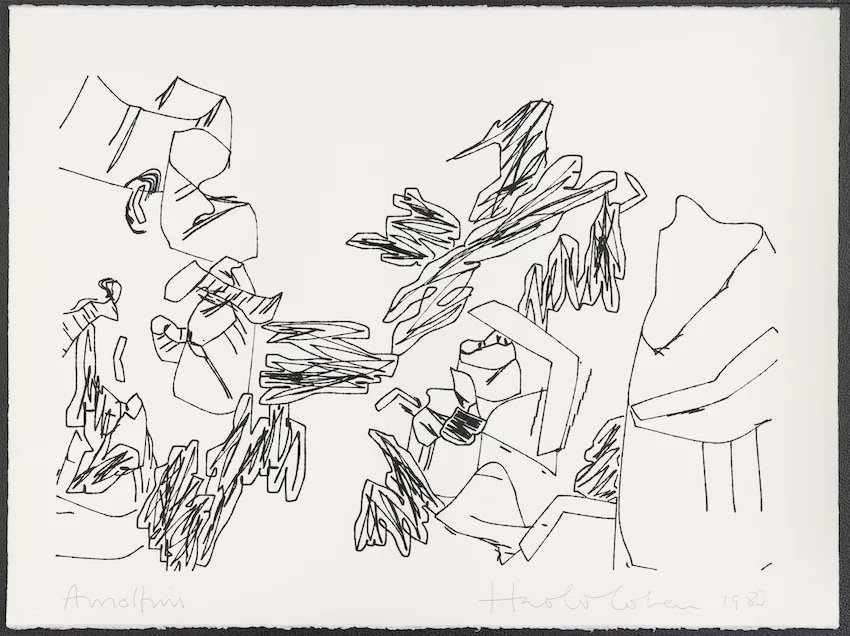

Working out of UC San Diego, Cohen utilized the CDC 3200 and punch cards to gather input. Cohen felt stifled by this process and decided to work with computers that he could program himself. Cohen’s first programs were rather simple, defined by a small set of rules that the computer composed into drawings, which were then drawn by a robot “turtle” which held a pen and crawled over the paper.

“In all its versions prior to 1980, AARON dealt exclusively with internal aspects of human cognition. It was intended to identify the functional primitives and differentiations used in the building of mental images and, consequently, in the making of drawings and paintings. The program was able to differentiate, for example, between figure and ground and inside and outside, and to function in terms of similarity, division and repetition. Without any object-specific knowledge of the external world, AARON constituted a severely limited model of human cognition, yet the few primitives it embodied proved to be remarkably powerful in generating highly evocative images: images, that is, that suggested, without describing, an external world.”

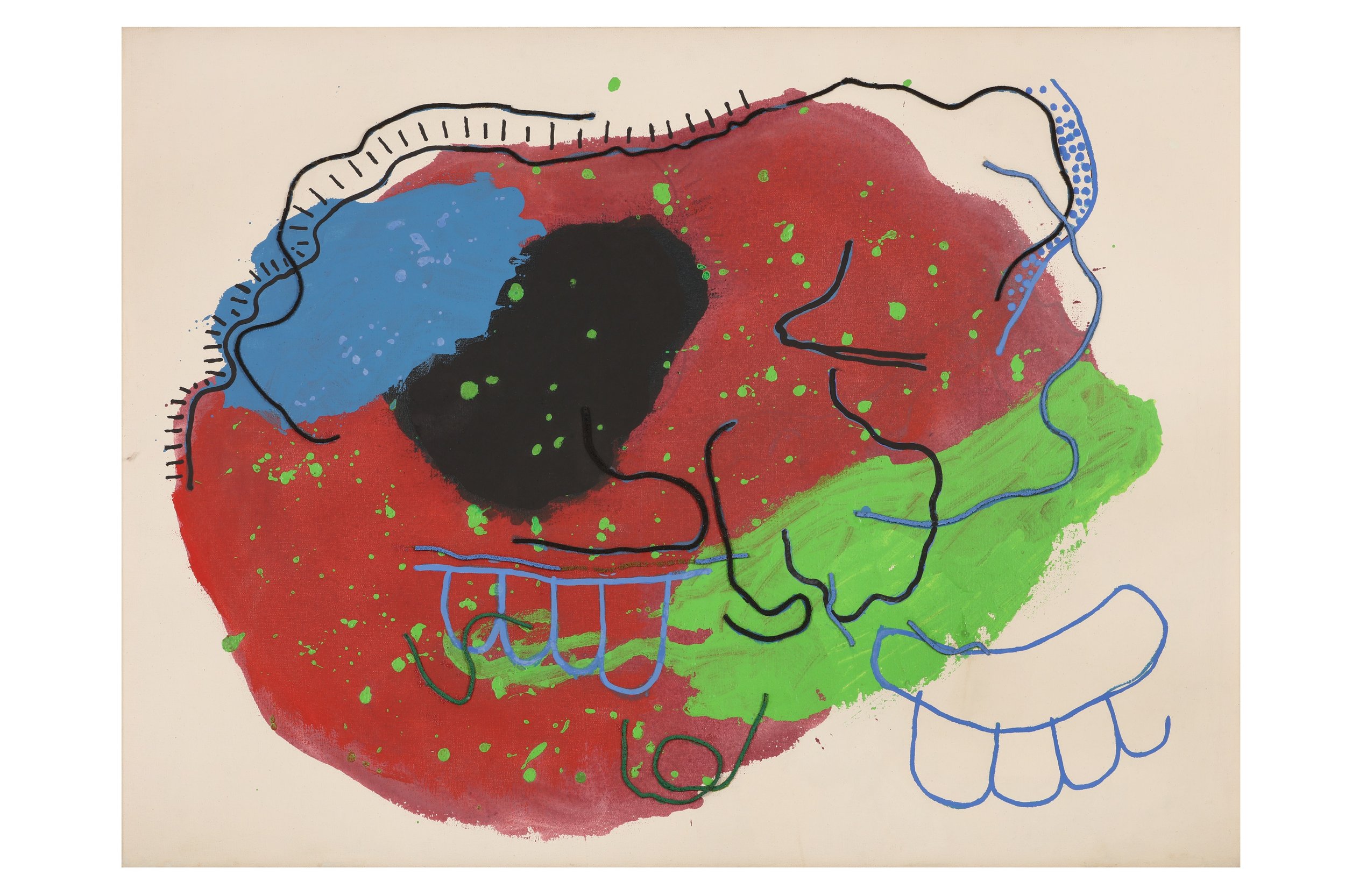

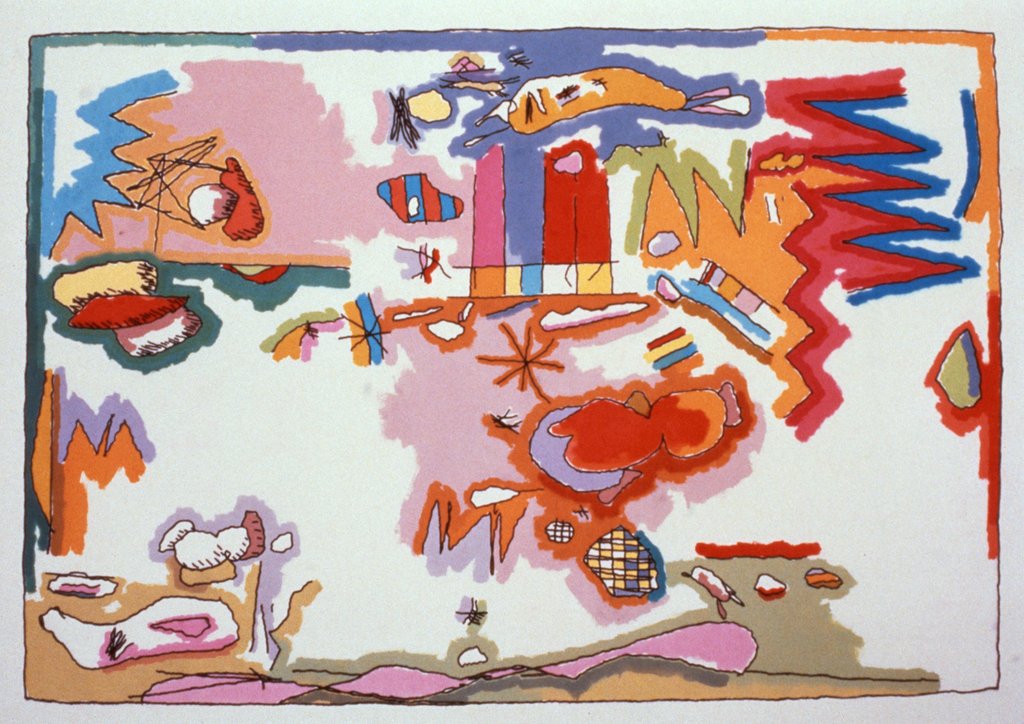

The drawings created by Cohen using AARON were relatively simple and primitive, resembling ancient petroglyphs. Cohen would add color by hand after the computer program finished drawing with the “turtle”, then later using sturdier robotic arms.

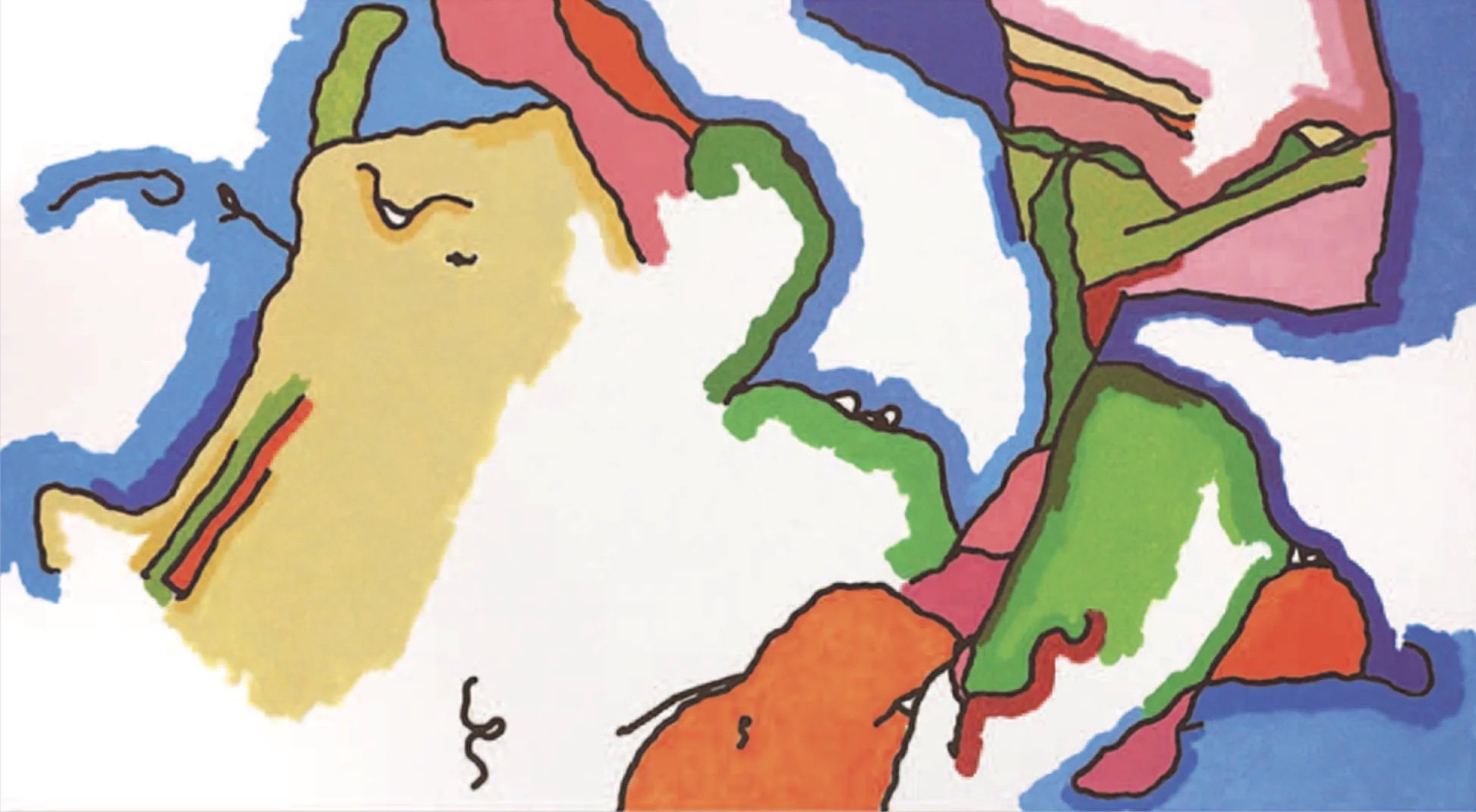

“In 1995 Cohen debuted a version of AARON that not only drew the forms, but could color them as well. The system, measuring almost 8 feet long and nearly 6 feet wide, used a vacuum table to hold the paper in place while an arm drew and then colored the forms. This required more complex software, which was only possible with Cohen’s evolution out of the C language into the lingua franca of artificial intelligence—LISP.”

Cohen examined the relationship between AI and the artist decades before our current debate. Cohen felt that the program was creative, but ultimately, he was the source of its creativity. He likened his relationship with AARON to that of Renaissance masters and their studio painters. As the program and robotic capabilities became more sophisticated, Cohen contributed less and less in a traditional media sense. He worked almost exclusively in the confines of the computer program, adding drawing and color.

These AI artworks are charming and you can sense the technological primitivism in the pieces. You can feel the limitations of the software, hardware, and robotics used to create them. You can also see the faint glimmer of future capabilities and how artists like Cohen remain on the cutting edge of technology. I especially like the early works of AARON, the black and white ones, that evoke feelings of a prehistoric society leaving traces behind simply to convey “I was here.” What will remain of our technological society in the distant future?

It is essential to look back on the history of computers and art to understand the present moment. As Marshall McLuhan said, “As the unity of the modern world becomes increasingly a technological rather than a social affair, the techniques of the arts provide the most valuable means of insight into the real direction of our own collective purposes.” Computers dominate our lives now and AI is on the rise, from customer service to advertising to art. However, I don’t think we need to fear the rise of the robots. AI will never replace the human creative spirit and artists will always stay on the cutting edge. I’ll leave you with one last McLuhan quote that seems especially prescient when examining Cohen’s decades old work, “Art at its most significant is a Distant Early Warning System that can always be relied on to tell the old culture what is beginning to happen to it.”